Suh Jeong Min, at the Venice Biennale

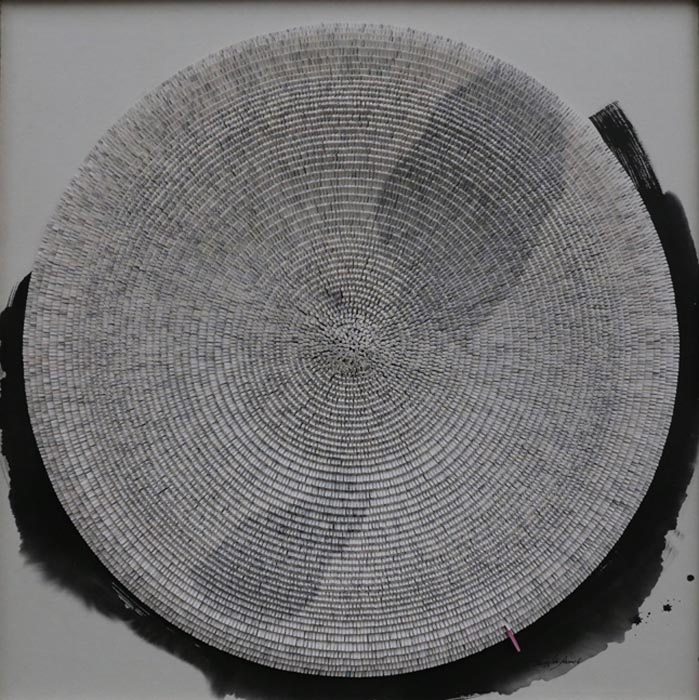

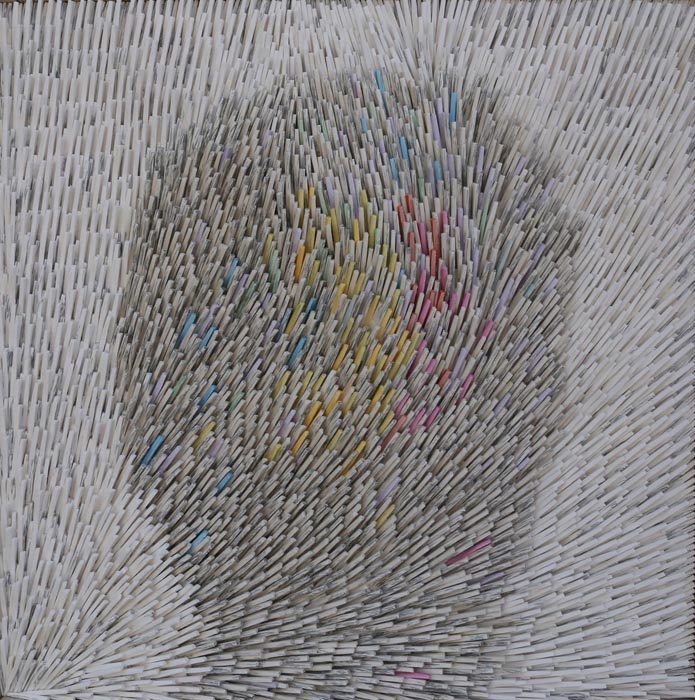

The artwork of Suh Jeong-min employs the timeless structures of geometry while simultaneously pursuing an idiosyncratic aesthetic that combines cultural references with unusual formal techniques. These elegant and somewhat imposing works are neither painting nor sculpture, yet have properties of both, and extend recent trends in art such as the privileging of material and the use of language into new territory. For some viewers, Suh’s artwork will arouse curiosity about Korean culture through its attractive, tactile surfaces, while others more familiar with his materials will find themselves rediscovering these materials in new and unexpected ways.

Suh builds up each artwork through an accumulation of discrete units of paper rolled into tubes or overlaid so that they resemble thin blocks of wood. Each one contains so many individual paper scraps compressed together that when they are cut by him their ends resemble the horizontal cross section of the trunk of a cut-down tree with its annual rings. These are affixed to the support by Suh with a rice-based glue in either afairly ordered way, or more randomly to create specific visual effects. He cuts each piece by hand, eschewing machinery for the intentional imprecision of the personal touch.

The paper Suh uses is called hanji, and is made from the inner bark of Mulberry trees. This paper is usually formed into laminated sheets that are pounded to compact the woodfibers, giving it great resilience and durability. The world’s oldest surviving wood block print, the Buddhist “Pure Light Dharani Sutra,” which is Korea’s National Treasure No. 126, was printed on hanji in c. 704 and is still in good condition. Hanji is so sturdy that it was used to make furniture such as cabinets and trays, and as a window covering.

Artworks

„XXXX“, YYxXX, xxxx

Suh Jeong Min

„XXXX“, YYxXX, 2004

Suh Jeong Min

„Tao 4“, YYxXX, xxxx

Suh Jeong Min

„Lines in Chorus I“, YYxXX, xxxx

Suh Jeong Min

„XXXX“, YYxXX, xxxx

Suh Jeong Min

Venedig Biennale

Suh Jeong Min